Oliver Stone’s 1989 Born on the Fourth of July

Oliver Stone’s body of work is a prime example of the limitations a one-note director brings to and defines his cinema. The difference between a “metteur en scene” (Stone) and an “auteur” (John Ford, who also made many war films, his theater being the Second World War) is how the former exploits a singular, timely subject –in Stone’s case, the Vietnam Conflict – while the latter expresses their subjects through a nuanced, timeless style. The “metteur”’s films inevitably become a function of plot, while the “auteur”’s become a function of style.

Considering how much of Stone’s filmography is studded with his so-called anti-war, anti-mainstream government sentiments, it may be hard for some to believe he dropped out of Yale to enlist in the army and fight in Vietnam. There, he was wounded twice and received several medals, including a Purple Heart and a Gold Star for Valor. His service also awarded him a strong distaste for war, what it does to those soldiers who do the fighting, and those who send them (as Phil Ochs once wrote and sang, “It’s always the old who lead us to the wars, it’s always the youngto fall … ”). It isn’t difficult, then, to recognize why Stone was attracted to Ron Kovic’s story. The true-life subject of Born on the Fourth of July (based on Kovich’s memoir and the screenplay adapted from it, co-written with Stone) was the son of military parents. When he came of legal age in the early months of the Vietnam War, he followed his family’s tradition of service and enlisted in the Marines. In 1965, he was shipped to Vietnam where, in a battle three years later, he was shot and, subsequently, paralyzed from the waist down. He, too, received a Purple Heart and a Gold Star for Valor. And he, too, became an anti-war activist. Stone expressed his sentiments through movies (1965’s Oscar-winning Platoon he wrote, produced, and directed); Kovic appeared at demonstrations and sit-ins and lectured to students on college campuses.

In 1976, the wounded veteran wrote what became a bestselling memoir that Al Pacino bought the rights to, intending to play Kovic onscreen. The script went through numerous revisions and frustrated with the slow pace of its development,Pacino eventually dropped out. The reason wasn’t because of any potential career-risking controversy – by this time, Vietnam was the most unpopular undeclared war in American history – but the financial pragmatism that has always defined Hollywood. The feeling in the industry was that Vietnam was old and bad news, a lost war everyone wanted to forget, and nobody would pay money to see it recreated in the movies.

After the success of his semi-autobiographical Platoon (1986), the highest-grossing film that year, won four Academy Awards and made stars out of Charlie Sheen andWillem Dafoe, Stone became the hottest, most sought-after director in Hollywood. He then announced he had acquired the rights and would co-write. direct andproduce the film through his own independent company, “Ixtlan” with Universal. The studio agreed to finance and distribute Born, believing Stone would make it a sequel to Platoon, but the project quickly took on a life of its own. Stone smartly focused on the debilitating price one soldier’s valor cost him that could never be repaid as a powerful metaphor for the country’s post-Vietnam psychic wounds he believed could never be healed.

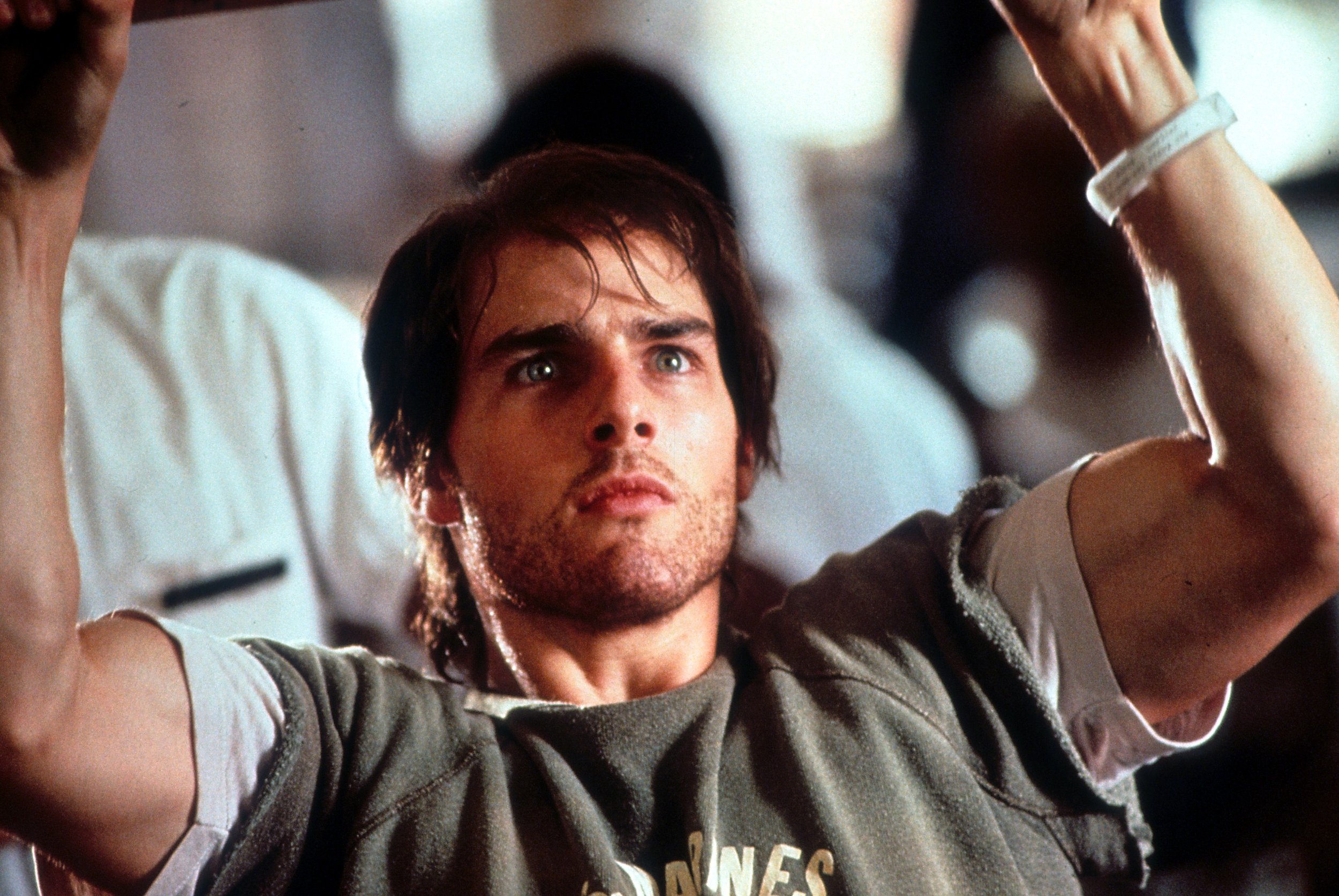

With an A-list director attached, every top actor in Hollywood now wanted to play Kovic, including finalists Sheen, Sean Penn, and Nicholas Cage. Stone eventually chose Tom Cruise, who’d become a superstar playing “Maverick” in Tony Scott’s 1986 Top Gun. The director had no love for that film, calling it a “fascist movie,” but believed Cruise’s name insured big box office returns. The star subsequently spent a year preparing for the role, visiting wounded veterans and sharing significant one-on-one time with Kovic. At one point, Stone wanted Cruise to be injected with a drug that would temporarily paralyze him, an idea reminiscent of the Method actor who played a murderer in a stage play and nearly strangled his co-star to death. Cruise made it clear he was an actor interested in playing paralyzed, not being paralyzed, and politely declined his director’s suggestion.

Stone’s, Cruise’s, and Universal’s gamble paid off. From a budget of $17 million, Born on the Fourth of July grossed $172 million in its initial release, was nominated for nine Academy Awards, and won two – Stone for Best Director and David Brenner and Joe Hutshing for Best Film Editing (Cruise was nominated for Best Actor but lost to Daniel Day-Lewis for his performance in Jim Sheridan’s My Left Foot).

Born on the Fourth of July, the film no studio wanted to make, proved once again Hollywood’s true mantra when it comes to making movies: “Nobody knows anything about anything.”

I have a personal connection to this film – Ron Kovic is a friend of mine. I first met him in the ‘70s at a rally protesting the Vietnam War. We were introduced by a mutual friend, the above-mentioned Phil Ochs, who was the subject of my first biography, Death of a Rebel: Starring Phil Ochs and a Small Circle of Friends.

I saw Ron often when I lived in Hollywood. He was, and still is, one of the most positive people I’ve ever met. Whenever our paths crossed, on a studio lot or, most often, in a restaurant we both frequented in Beverly Hills, we always fell into spirited conversations about films, books, food, politics, and other assorted pleasures of the mind and body. Ron is an inspiration, not just to me, but to every person who struggles to overcome what is perceived as a bad hand dealt, an impossible fate. I invited him to come to this screening, but for his advanced age and the difficulties he has traveling in his condition, he was sorry to say he couldn’t make it this timebut assured me he would be with us in spirit.

A Word About the Academy Awards

It arrives every winter, like the flu, with a fever all its own. Hollywood is the most self-congratulatory business in the world, where simply doing one’s job makes everyone who works in the industry eligible to take home an “Oscar” and all the Wolfgang Puck chocolate cigars they can eat. What I always find so ridiculous about the Academy is that it always uses this night to convince everyone that Hollywoodmakes “quality” films – Brady Corbet’s holocaust horror show The Brutalist andEdward Berger’s behind-the-scenes Vatican Conclave, to name two of this year’s Best Picture nominees – while virtually ignoring the tsunami of sequels, supermen and spider people that paves the industry’s yellow brick road.

It is ironic, perhaps, that Anora, an independent film shot entirely in Brighton Beach, a lower-middle-class, predominantly Russian ex-pat-inhabited Brooklyn neighborhood adjacent to Coney Island, took home five Academy Awards, despite it being a film almost no one saw. It is the lowest-grossing film ever to win Best Picture. It earned $15 million (what Wicked takes in every time it’s shown). In Hollywood arithmetic, a film needs to take in twice what it costs to break even. You do the math. While it didn’t make anyone involved with the film wealthy, Anora set up its director/editor/screenwriter Sean Baker and the hitherto virtually unknown Mikey Madison to name their own prices going forward. Millionaires of the movie worldunite! As I told anyone within earshot last October, when I first saw it at the New York Film Festival, Anora would win the Best Picture Oscar. I was thoroughly charmed by this low-rent indie that turns the Cinderella fairy tale inside out and backward. (We’ll be showing Anora as part of our next cycle, a “mini-New York Film Festival” in the latter half.)

As for the awards show itself, it is always fairly horrible, too long, unfunny, with so-called “celebrity” hosts who have nothing to do with film and only middling success on TV. Gone are the days of Bob Hope, at home on a film set, radio and television studio. And yet, I am addicted to the Oscars. Four hours of jokes that fall flat, endless skits and songs, listless streakers, angry slaps, “Envelopegate” slip-ups (like the time they gave the Best Picture Oscar to the wrong film) notwithstanding, it remains one of the last places outside of sports and the news where one may experience true “live” TV in all its bleeping glory. I don’t think I’ve missed an Oscar show since I was old enough to care about them, a kid sitting on the floor of my parents’ living room watching them, glued to the black and white cabinet television. I’ve seen them in person while living in Hollywood, on TV from my place in New York City, my home in upstate New York, in hotels in Guatemala, Paris, London, andBeijing (where they start at seven in the morning; orange juice, omelets, and Oscars, who could ask for anything more? While I rarely agree with the choices made by the Academy’s voters, to me, it is, on any given year, the best drama produced by Hollywood, from Hollywood, for Hollywood (the rest of us, the faithful voyeurs who pay for the privilege at the box-office).

One final thought. Why do so many actresses win “Best” Oscars (lead and supporting) for playing hookers? I heard someone recently list the many award-winning performances that were based on prostitutes, including, in part, Donna Reed (Fred Zinnemann’s 1954 From Here to Eternity, Jane Fonda (Alan Pakula’s 1972 Klute), Susan Hayward (Robert Wise’s 1958 I Want to Live), Jo Van Fleet (Elia Kazan’s 1955 East of Eden), Shirley Jones (Richard Brooks’ 1960 Elmer Gantry), Elizabeth Taylor (Daniel Mann’s 1960 Butterfield 8), Mira Sorvino (Woody Allen’s 1995 Mighty Aphrodite), Charlize Theron (Patty Jenkins’ 2003 Monster), and many more. Alas, this year’s winner, Ms. Madison, won for playing, aha, a stripper in a club who turns tricks for money.

-Marc Eliot

Resident Film Curator